Author: Gershon Ben Keren

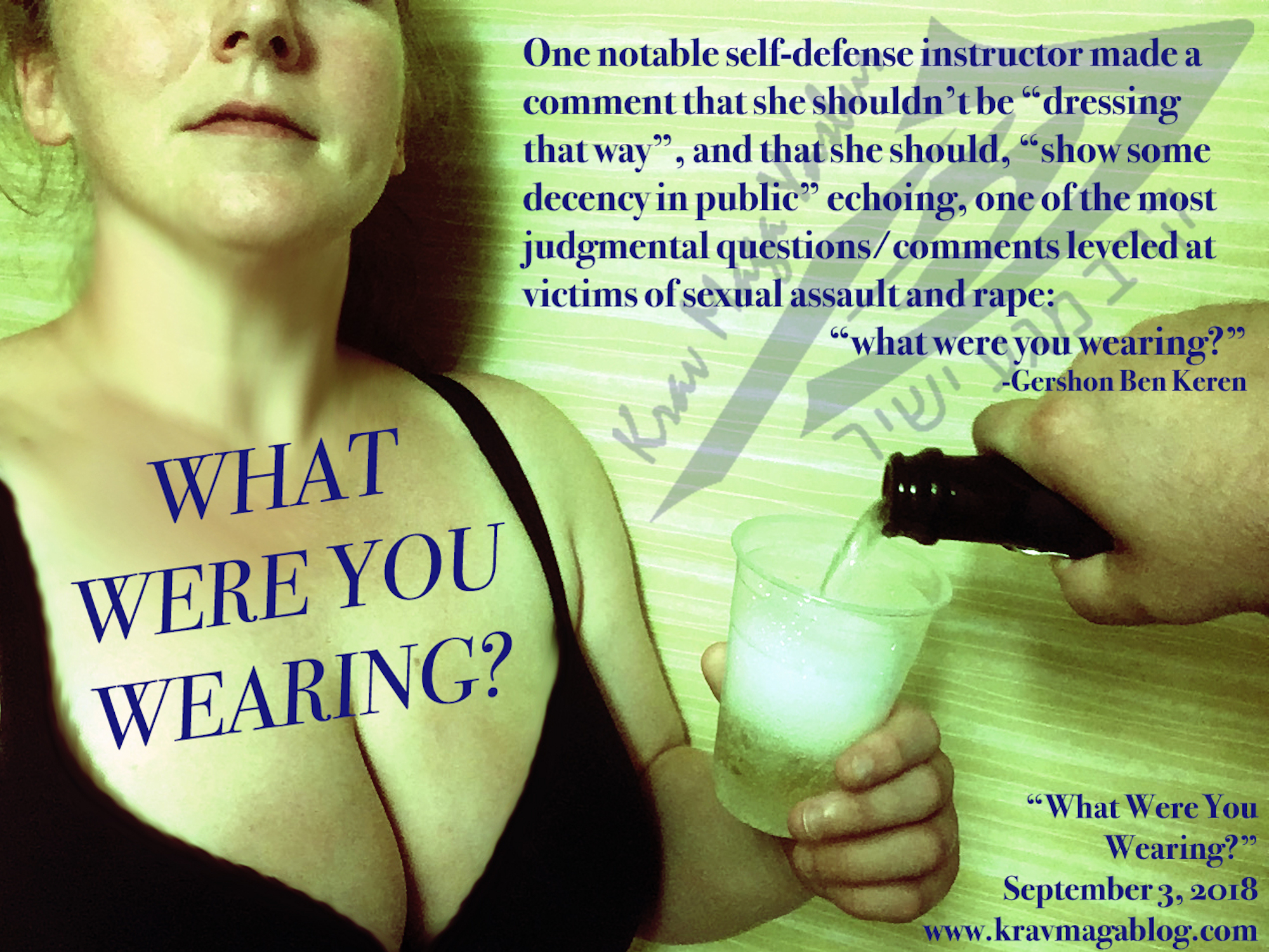

Several weeks ago, I wrote an article on campus safety for young women preparing to go to college for the first time – and in preparation for a free annual campus safety seminar that my school puts on. The accompanying meme/picture came from a photo shoot, that we did awhile back, which was set at a college style party, and featured a female student in a crop-top (we asked her to bring the type of clothes she’d where to such a party). One notable self-defense instructor made a comment that she shouldn’t be “dressing that way”, and that she should, “show some decency in public” echoing, one of the most judgmental questions/comments leveled at victims of sexual assault and rape: “what were you wearing?” i.e. that victims of such assaults, somehow attract the attention of sexual predators because of what they wear and/or that men, who do not “normally” engage in predatory behavior are unable to control themselves sexually, when confronted by a woman exposing flesh (following this argument, beaches and swimming pools would perhaps be the most common locations for sexual assaults — which they aren’t…). Maybe naively, I’d thought that our industry had accepted that rape is primarily about power, anger and control, and not about sex – sex being the tool by which these elements are expressed; something that Dr. Nicholas Groth’s research in the 1970’s established. Research by Workman and Freeburg, and others, has shown that in certain populations, both men and women believe and judge victims of sexual assault to be in some way responsible, based on the clothing they are wearing. But if we examine the psychology of rape, clothing is rarely, if ever, a significant factor in victim selection; and we are doing a great disservice to women – in a multitude of ways — if we in the self-defense community are elevating it as a risk-factor. In this article, I’d like to examine how women’s self-defense programs may not accurately reflect reality, and how as instructors we may be guilty of promoting and reinforcing stereotypical ideas concerning rape and sexual assault.

A number of studies have shown that women are most likely to be raped, by someone they know (often an ex-partner, or somebody they previously had an intimate relationship with), in their home or somebody else’s; and least likely to be successful in fighting off such attacks. It would appear that women have been more successful in defending themselves against stranger rapes, and when the assault took place outside (training not being a significant or notable factor). When we consider these facts, Rape and Sexual Assaults, become socially complex affairs, that involve familiar people in familiar locations – this is reflected in the reporting of rape to the Police, with research by De Mont et al, showing that women raped by a stranger are twice as likely to report the assault to Police, than those who are raped by someone they know. If we consider that most assaults take place in the home, clothing can be seen as an irrelevant factor, as most people dress casually in such settings. We know that rape is born out of masturbatory fantasies, and so when the assailant is someone that the person being victimized knows, it is likely that a certain degree of planning, preparation and orchestration is involved in the assault – the assailant will be able to create and determine the opportunity, etc. If our teaching/training doesn’t reflect this, and we simply create scenarios where a person is attacked, whilst walking alone (late at night), we are reinforcing the idea to our students that this is where/when they are most at risk, which isn’t the case. Obviously, solutions to such incidents need to be taught, but not at the exclusion of the more likely types of incidents that women may have to face. We may also have to convince our audience, that being assaulted in their home, by someone they know, is the most likely scenario they are going to face, as people have a natural denial when faced with statistics, believing that although they may be true, they don’t apply to themselves personally e.g. women in general are most likely to be sexually assaulted by someone they know, in their home, but I’m most likely to be raped by a stranger in an outside location, etc. Presenting socially complex scenarios, in a way that doesn’t create paranoia e.g. a fear that every male friend and acquaintance is a potential rapist, etc., and is realistic, is challenging, but to do otherwise is to do a disservice to those who look on us as the experts, and those who should be in possession of the facts. It also requires us to become educated as to grooming processes, and how to identify them, rather than simply look at physical self-defense.

Another factor that often gets brought up when looking at rape, is the relationship between alcohol and sexual assault; both from the perspective of the assailant, and the person they’ve victimized. One myth that many men who have been accused of rape try to cling to, is that they wouldn’t have committed a sexual assault unless drunk i.e. it was the alcohol that turned them into a sexual predator – it wasn’t their fault, it was the drink. This argument is no different to that of blaming the person victimized, because of the way she dressed e.g. it’s not the assailant’s fault, because they couldn’t help themselves. If you don’t have a desire to engage in forced/non-consensual sex, alcohol won’t change that – it may however embolden you to act if you do; Brock Turner was already a sexual predator, before he had his first drink at the party where he met the woman he raped. There is obviously a case to be made that alcohol consumption makes both genders more vulnerable, and easier to exploit, however most of the research done regarding the relationship between alcohol and rape, such as that by Harrington et al, has been conducted on University Campuses, and so can only really be used in relationship to this specific population, etc., who lead a specific lifestyle, and may use alcohol differently to the general population.

One major reason that we as educators need to be actively debunking these rape myths, is that we may be inadvertently causing women to see themselves as being responsible for their own assaults e.g. if we promote the myth that a woman wearing a short skirt is, “asking for it”, then if a woman is sexually assaulted when wearing such clothing, she may believe that she is in someway responsible or to blame, and feel that she will either not be believed (that somehow she was looking for this type of attention), or be judged for dressing that way, etc. If we reinforce the idea – by our training – that women aren’t, or are not likely to be assaulted by someone they know, it may be that we inadvertently communicate the message, that what happened doesn’t really constitute rape, etc. If we teach women’s self-defense and personal safety, we have a responsibility to make sure that our training reflects reality. If it doesn’t, then despite our best intentions, we may actually be part of the problem, rather than offering any solutions.